By: ANSAR AHMED ULLAH

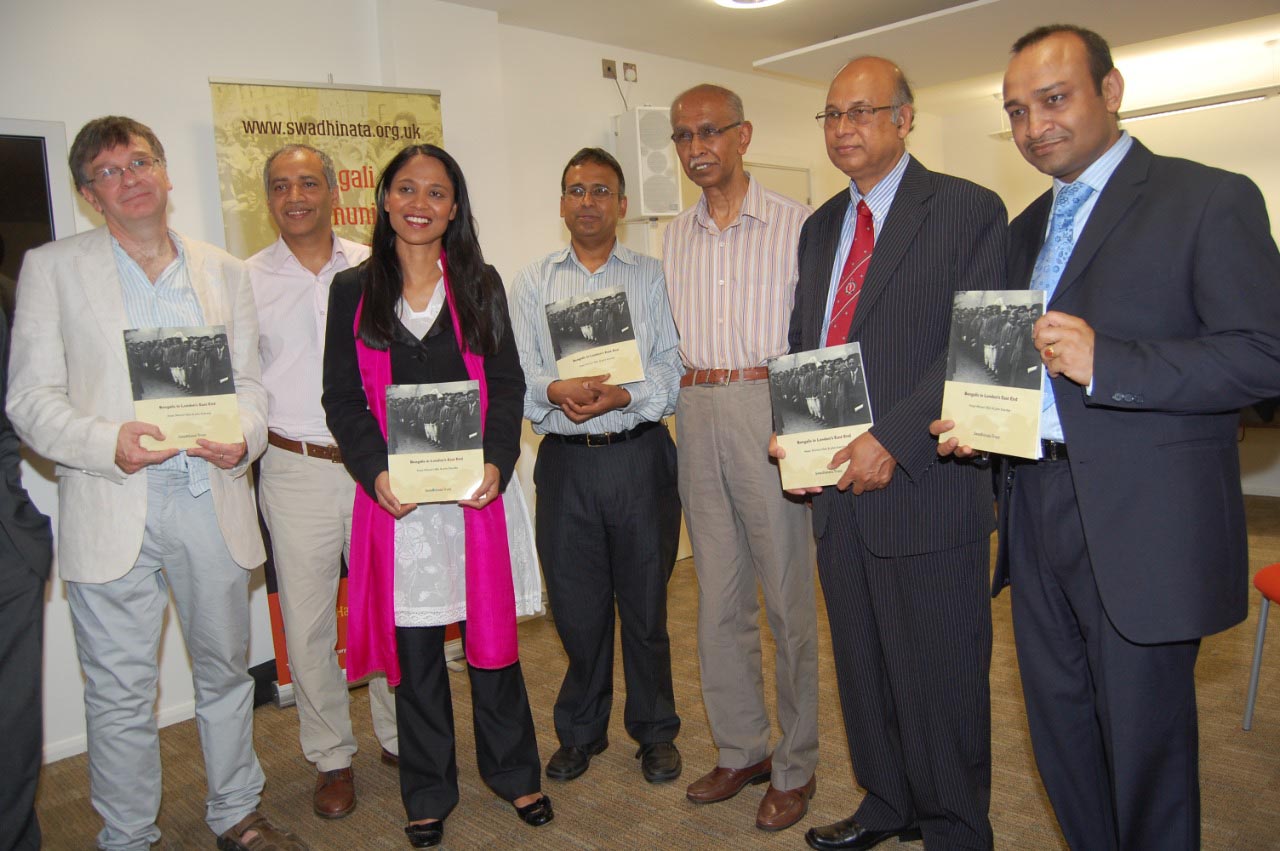

In 2005 the Swadhinata Trust embarked on an oral history project, Tales of Three Generation of Bengalis in Britain, which voiced three generations’ experience of being Bengali in multicultural Britain. The project consisted of a collection of fifty-eight oral histories with a focus on three specific themes: ‘roots and memory’ (dialogue between first and third generation on the history of Bangladesh and the 1971 war of independence); ‘community creativity’ (dialogue between second and third generation on welfare and community involvement in the UK, from the 1970s-80s) and finally ‘popular culture: between tradition and innovation’ across three generations, mainly focussing on traditional and more recent British Bengali musical heritage, from the 1970s-80s.

According to the 2011 census, 450,000 Bengalis (from Bangladesh, excluding West Bengal) currently live in the UK and Inner London, constituting the third largest ethnic group after the White British. Despite their substantial presence within the ‘global city’ of London and in urban centres across the country, such as Luton, Birmingham and Manchester, oral histories of their settlement within this country have been limited to a few pioneering publications. Many of the first settlers are now elderly. Sadly some have already passed away, and their memories and experiences are being lost as their testimonies have not been recorded and preserved.

The theme ‘roots and memory’ we looked at was – the history of Bangladesh and the 1971 war of independence. So we began with people’s memories of East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) and the events leading to the Liberation War.

The interviews made it clear the Liberation War was not just fought in the Bengal delta. By 1971 a small but growing Bengali community had been established in the UK, and in many places, such as London, Luton, Birmingham and Manchester, they worked with or lived near Pakistanis, who had migrated from the Punjab and Kashmir. Interestingly, Bengalis were active in political activity before 1971 as they supported greater autonomy for East Pakistan in 1966 and campaigned for East Pakistan’s leader, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s release after he was arrested in 1968.

During the War of Bangladesh in 1971, the community played an essential role in highlighting the atrocities in Bangladesh, lobbying the British government and the international community and raising funds for the refugees and the Bengali freedom fighters. It is said that some people donated their entire week’s salary, and at least in one case, a woman donated her entire wedding gift of gold jewellery. There were even people willing to go and fight in Bangladesh. However, many Bengalis talked about the prejudice they faced from Pakistanis in the UK. There were even physical clashes between Pakistanis and Bengalis as the war started.

Many Bengalis spoke about the prejudice they faced from Pakistanis in the UK. There were even physical clashes between Pakistanis and Bengalis as the war began.

In the second theme, ‘Community Creativity, ’ we focussed on the emergence of the second generation of Bengali community activists and their entry into mainstream politics during the late 1970s and early 1980s. Bengali community politics moved away from preoccupations with political struggles in Bangladesh, which were discussed in the first strand. An alliance was forged between some of the first generations who we interviewed. They seized the opportunity of gaining access to the local political system and state funding channelled through the local borough council, the Greater London Council (GLC) and the Inner London Educational Authority (ILEA).

They also saw the importance of building alliances with activists outside the Bengali community, such as other ‘Asians’ from Hackney, Newham, Camden & Southall and those from the White majority, such as Caroline Adams, Darek Cox, Mark Adams, Peter East, Terry Fitzpatrick, John Newbigin, John Eversley, Dan Jones, Cathy Forrester (Peters), Rev Kenneth Leech and Claire Murphy. Through various ‘redevelopment’ schemes – the Spitalfields Project and Bangladeshi Educational Need in Tower Hamlets (BENTH) are two examples discussed here – government money began to flow into Spitalfields and other wards where the Bengali population was rapidly expanding.

Although mainly Bengali men contributed to these developments, the interviews with Mithu Ghosh, Shila Thakor and Claire Murphy reveal the vital role played by women and the influence of debates about women’s rights and gender equality.

The interviews also look beyond this period of Bengali community formation and political mobilisation to events leading up to the contemporary situation in Brick Lane. They point to the crucial economic and social changes – the decline of the garment industry, the expansion of the service sector, especially restaurants and shops, and the emergence of a third generation where the highly educated pull away from those without prospects. In Spitalfields, the impact of the ‘global city’ was felt by the gentrification of the conservation areas by wealthy white ‘immigrants’, the colonisation by high technology, advertising, media and the arts sector, and the arrival of the City of London businesses and across the borough generally the transformation of the derelict docks in the south into the gleaming Manhattanesque landscape of Canary Wharf and the new housing for white middle-class newcomers on the Isle of dogs and other southern localities. Brick Lane is still the centre of Bengali enterprise, but it has become a global icon, and attempts by local Bengali entrepreneurs and others to market the area’s Banglatown – the East End’s answer to the West End’s Chinatown.

In the third theme, ‘Popular Culture: Between tradition and innovation,’ we focussed on traditional and more recent British Bengali musical heritage from the 1970s-1980s. The rise of Asian music started in the 1970s by Biddu, Steve Coe and Sheila Chandra, but in the late 80s, the British Asian youth first started to create a new musical genre by combining dance music with the music of their parent’s generation. The youth grew up in an environment of racial violence and political struggle for self-identity while drawing strength from street culture and Asian roots. They took pride in their music as they could claim it as their own – neither white nor music imported from the Indian sub-continent. The artists, who emerged from this period, became some of the greatest Asian artists Britain has seen. Some of these artists (Asian Dub Foundation, Joi, State of Bengal and Osmani Soundz) are of Bengali origin and are the true pioneers of the Asian underground scene.

At the same time, a number of people were practising music from Bangladesh and managed to establish themselves over here. There is also a strong following in Baul music as most Bengalis here are from rural backgrounds. In 1985 UNESCO declared the Baul music of Bangladesh a National Heritage. Another trend is the third-generation British Bengalis practising contemporary Bengali music in the UK.

We explored these developments through interviews where our participants explained their involvement with and approach to music, the influences on their music and their relationship with their music teachers, the role models which influenced them, their musical preferences in terms of instruments and musical styles, the festivals, events, performances which they participate in, their songs, released singles and albums, their interest in traditional music from Bangladesh, the mixing of different musical styles and their views about young musicians and the younger generation.

Finally, no comprehensive history of the Bengali community activism in the UK has been documented. A few individuals and organisations, including Altab Ali Foundation & recently Four Corners, have attempted to document the history of the contribution of the Bengali diaspora community. Though Swadhinata Trust’s attempt to record memories of the community involvement through the oral history project added new information, there are, of course, still many facts to be revealed about the Bengali-led anti-racist mobilisation and the movement that took place in the UK.

By: ANSAR AHMED ULLAH

In 2005 the Swadhinata Trust embarked on an oral history project, Tales of Three Generation of Bengalis in Britain, which voiced three generations’ experience of being Bengali in multicultural Britain. The project consisted of a collection of fifty-eight oral histories with a focus on three specific themes: ‘roots and memory’ (dialogue between first and third generation on the history of Bangladesh and the 1971 war of independence); ‘community creativity’ (dialogue between second and third generation on welfare and community involvement in the UK, from the 1970s-80s) and finally ‘popular culture: between tradition and innovation’ across three generations, mainly focussing on traditional and more recent British Bengali musical heritage, from the 1970s-80s.

According to the 2011 census, 450,000 Bengalis (from Bangladesh, excluding West Bengal) currently live in the UK and Inner London, constituting the third largest ethnic group after the White British. Despite their substantial presence within the ‘global city’ of London and in urban centres across the country, such as Luton, Birmingham and Manchester, oral histories of their settlement within this country have been limited to a few pioneering publications. Many of the first settlers are now elderly. Sadly some have already passed away, and their memories and experiences are being lost as their testimonies have not been recorded and preserved.

The theme ‘roots and memory’ we looked at was – the history of Bangladesh and the 1971 war of independence. So we began with people’s memories of East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) and the events leading to the Liberation War.

The interviews made it clear the Liberation War was not just fought in the Bengal delta. By 1971 a small but growing Bengali community had been established in the UK, and in many places, such as London, Luton, Birmingham and Manchester, they worked with or lived near Pakistanis, who had migrated from the Punjab and Kashmir. Interestingly, Bengalis were active in political activity before 1971 as they supported greater autonomy for East Pakistan in 1966 and campaigned for East Pakistan’s leader, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s release after he was arrested in 1968.

During the War of Bangladesh in 1971, the community played an essential role in highlighting the atrocities in Bangladesh, lobbying the British government and the international community and raising funds for the refugees and the Bengali freedom fighters. It is said that some people donated their entire week’s salary, and at least in one case, a woman donated her entire wedding gift of gold jewellery. There were even people willing to go and fight in Bangladesh. However, many Bengalis talked about the prejudice they faced from Pakistanis in the UK. There were even physical clashes between Pakistanis and Bengalis as the war started.

Many Bengalis spoke about the prejudice they faced from Pakistanis in the UK. There were even physical clashes between Pakistanis and Bengalis as the war began.

In the second theme, ‘Community Creativity, ’ we focussed on the emergence of the second generation of Bengali community activists and their entry into mainstream politics during the late 1970s and early 1980s. Bengali community politics moved away from preoccupations with political struggles in Bangladesh, which were discussed in the first strand. An alliance was forged between some of the first generations who we interviewed. They seized the opportunity of gaining access to the local political system and state funding channelled through the local borough council, the Greater London Council (GLC) and the Inner London Educational Authority (ILEA).

They also saw the importance of building alliances with activists outside the Bengali community, such as other ‘Asians’ from Hackney, Newham, Camden & Southall and those from the White majority, such as Caroline Adams, Darek Cox, Mark Adams, Peter East, Terry Fitzpatrick, John Newbigin, John Eversley, Dan Jones, Cathy Forrester (Peters), Rev Kenneth Leech and Claire Murphy. Through various ‘redevelopment’ schemes – the Spitalfields Project and Bangladeshi Educational Need in Tower Hamlets (BENTH) are two examples discussed here – government money began to flow into Spitalfields and other wards where the Bengali population was rapidly expanding.

Although mainly Bengali men contributed to these developments, the interviews with Mithu Ghosh, Shila Thakor and Claire Murphy reveal the vital role played by women and the influence of debates about women’s rights and gender equality.

The interviews also look beyond this period of Bengali community formation and political mobilisation to events leading up to the contemporary situation in Brick Lane. They point to the crucial economic and social changes – the decline of the garment industry, the expansion of the service sector, especially restaurants and shops, and the emergence of a third generation where the highly educated pull away from those without prospects. In Spitalfields, the impact of the ‘global city’ was felt by the gentrification of the conservation areas by wealthy white ‘immigrants’, the colonisation by high technology, advertising, media and the arts sector, and the arrival of the City of London businesses and across the borough generally the transformation of the derelict docks in the south into the gleaming Manhattanesque landscape of Canary Wharf and the new housing for white middle-class newcomers on the Isle of dogs and other southern localities. Brick Lane is still the centre of Bengali enterprise, but it has become a global icon, and attempts by local Bengali entrepreneurs and others to market the area’s Banglatown – the East End’s answer to the West End’s Chinatown.

In the third theme, ‘Popular Culture: Between tradition and innovation,’ we focussed on traditional and more recent British Bengali musical heritage from the 1970s-1980s. The rise of Asian music started in the 1970s by Biddu, Steve Coe and Sheila Chandra, but in the late 80s, the British Asian youth first started to create a new musical genre by combining dance music with the music of their parent’s generation. The youth grew up in an environment of racial violence and political struggle for self-identity while drawing strength from street culture and Asian roots. They took pride in their music as they could claim it as their own – neither white nor music imported from the Indian sub-continent. The artists, who emerged from this period, became some of the greatest Asian artists Britain has seen. Some of these artists (Asian Dub Foundation, Joi, State of Bengal and Osmani Soundz) are of Bengali origin and are the true pioneers of the Asian underground scene.

At the same time, a number of people were practising music from Bangladesh and managed to establish themselves over here. There is also a strong following in Baul music as most Bengalis here are from rural backgrounds. In 1985 UNESCO declared the Baul music of Bangladesh a National Heritage. Another trend is the third-generation British Bengalis practising contemporary Bengali music in the UK.

We explored these developments through interviews where our participants explained their involvement with and approach to music, the influences on their music and their relationship with their music teachers, the role models which influenced them, their musical preferences in terms of instruments and musical styles, the festivals, events, performances which they participate in, their songs, released singles and albums, their interest in traditional music from Bangladesh, the mixing of different musical styles and their views about young musicians and the younger generation.

Finally, no comprehensive history of the Bengali community activism in the UK has been documented. A few individuals and organisations, including Altab Ali Foundation & recently Four Corners, have attempted to document the history of the contribution of the Bengali diaspora community. Though Swadhinata Trust’s attempt to record memories of the community involvement through the oral history project added new information, there are, of course, still many facts to be revealed about the Bengali-led anti-racist mobilisation and the movement that took place in the UK.